Nueltin Lake

Imagine the drama! Chief Chetoga of the Ojibway knows that after six years of relative plenty there is going to be a winter of starvation, because that is how these things go. So he sends his best hunter, Baluk, off in search of enough meat for winter. But enroute Baluk wants to check in on the chief's hot daughter, Neewa, who is off trapping partridges. And a good thing he did, because when Baluk meets up with Neewa she is cornered on the edge of a cliff by a huge bear.

Baluk slays the beast and takes its cubs back to the village as gifts for Neewa's little brother Cheeka. This fans the flames of Neewa's ardour towards Baluk, which infuriates the evil medicine man Dagwan, who also has his eye on Neewa. She being hot and all.

Over the course of 84 minutes Baluk and Dagwan fight for the favours of Neewa while Chetoga tries to keep his people from starvation - mostly by marching the tribe north to the Crossing of the Caribou, where the mighty caribou migration ensures plenty to eat but it's rather cold all the time.

The film was The Silent Enemy, a totally ironic title for what was to be essentially the last big budget Hollywood blockbuster of the silent film era. When production began, silent was a thing. By the time it was released two years later, silent was no longer a thing. The producers hastily put in some talkie dialogue in post - "Chief" Chauncey Yellow Robe (the stage name of Canowikacte, Kill in Woods, of the Sicangu Lakota Oyate in South Dakota), who played Chetoga, did a sound-on-film speech at the beginning of the film introducing the plot, and some chants throughout the film were added. As recently as 2012, a new score was composed for the film by Siegfried Friedrich. But, while a critical success, the film was kind of a box office flop because by the time it came out, people had been going to theatres to see and hear Al Jolson sing jazz for three years, and were currently watching Groucho, Harpo, Zeppo and Chico mug with Lillian Roth with scratchy voice and full orchestration.

But the film was still notable for several things. For one, it used upwards of two hundred first nations actors and walk-ons. None of the actual actors were technically Ojibwe, but still, using indigenous actors at all was fairly ground breaking. The film was also shot entirely on location in the wilds of Canada - in the "timber limits" outside Arnprior, according to The Motion Picture Daily, some forty miles west of Ottawa. Although the more observant amongst the crew and certainly all of the Algonquin/Ojibwe walk-ons would realize they were actually filming in Temagami, some two hundred fifty miles past Arnprior where there are trees and stuff. But the problem with both Arnprior and Temagami, as far as the plot of the movie was concerned, was the conspicuous lack of Caribou for the big migration scene.

Rangifer tarandus, Reindeer to some, and Caribou to others, frequent the arctic, subarctic, tundra and boreal regions all around the north pole. They come in several sub-species. The smallest, R.t. platyrhynchus, the Svalbard Reindeer, are the reindeer that Santa uses. They are at most 90 kilos and are found in the far north of Norway. The largest R. tarandus is the Boreal Woodland Caribou, R.t. caribou. This is the one you might find on a Canadian quarter. It can weigh in at an impressive 210 kilos and at one time was to be found throughout the boreal forests of Canada and even as far south as the States. At present, though, the Canadian boreal forest is being harvested and otherwise chopped up, limiting the caribou's mobility and making them susceptible to starvation and predation. The estimated 34,000 boreal caribou remaining are in a threatened state, and only 17 of the 57 existing wild populations are considered to be self-sustaining. Nonetheless, back in the post-classical era of Ojibwe history, these are the caribou that would have been found in the territory occupied by Baluk, Dagwan, Chetoga, his hot daughter Neewa, and the rest of the Ojibwe nation. The trouble, of course, is that R.t. caribou does not migrate, nor gather in any significant concentrations for any other purpose.

The caribou that the script writers (W. Douglas Burden, Richard Carver and Julian Johnson) were thinking of would have been the barren-ground caribou, R.t. groenlandicus. They're about halfway in size between the Svalbard and boreal sub-species. As the name implies, they live on barren ground above the tree line (mostly in Nunavut and the North West Territories) which is fine in the summer, but not so much in the winter. And so they have to migrate twice a year, south in the fall to their wintering grounds below the tree line, where there is some shelter from the winds and a little lichen to eat, and then north again in the spring to have their calves in the summer abundance to be found to the north. The various herds (eight of them) are named after the areas where they have their calves. So, for instance, the Qamanirjuaq herd has for their calving grounds Qamanirjuaq Lake (Huge Lake Adjoining a River at Both Ends), two hundred or so kilometers due west of Rankin Inlet, and five hundred or so kilometers north-east of Windy River, which flows out of Windy Lake and into Nu-thel-tin-tu-ch-eh (sleeping island lake), which trappers anglicized to Nueltin Lake. These two lakes are at the extreme south end of Nunavut, and the land between them makes a kind of a sheltered peninsula of sorts, roughly funnel-shaped. And it is through this peninsula that the great caribou migration of the Qamanirjuaq herd traverses twice a year. But to get through it they have to cross the Windy River, and the nature of that river is such that the caribou concentrate in a couple of spots to cross it as they journey to and from the "Land of the Little Sticks".

This land is the tree line, or the northern extent of the trees and the southern extent of the tundra. It is also the northern extent of the Etheneldile-dene (caribou-eating people) and the southern extent of the Inland Inuit people. The treeline, and therefore the border, shifts from time to time north and south depending on weather but is generally a little north of Nueltin Lake. So the concentration of animals during the migration, and the further concentration brought about by the unique topography around Nueltin Lake, have been of vital importance to two distinct populations of people for thousands of years. And, for one brief period in the fall of 1928, it was of vital importance to a film crew wanting to capture some footage for The Silent Enemy.

This film crew was headed by none other than Ilia Tolstoy, the grandson of the author of War and Peace. He was a good choice for the assignment, because ever since leaving Russia he had been making quite the name for himself as an adventurer. His travels would take him to such disparate places as Tibet, Alaska and The Pas, Manitoba. That is as far north as one could travel by train in 1928. From there it was just shy of one hundred portages to get to a little log cabin near where the fall migration of caribou between Windy and Nueltin Lakes would take place. Or not.

The winter of 1928-29 would turn out to be another in a string of winters when the caribou failed. Tolstoy would spend five months in the bush prior to returning to civilization empty handed. There were a few animals, but in low enough numbers that they could easily avoid anyone attempting to shoot them, even with cameras. Footage for the film would end up coming from a reindeer farm in Alaska. It was highly disappointing for Ilia. But it was a matter of considerably more import to the local Dene and Inuit. True to the script that they were perhaps better suited to be in than the Ojibwe of the boreal forest, the failure of the caribou meant starvation.

The caribou migration, which so far as anyone knows was entirely stable for thousands of years, started to get a little sporadic in the latter part of the 19th century. This would be, coincidentally, around the time that cartridge rifles were coming into widespread use, having been mass produced for the American civil war. Whether or not that enters into it, it remains that the caribou were either becoming fewer, or wiser. The vast herds were getting harder to find. As one HBC report had it at nearby Reindeer Lake, "Caribou seen each year from 1874 till 1884: none seen from 1885 until the autumn of 1889.". Tolstoy himself felt that there were still vast herds of the animals, they were simply avoiding places where there were people.

But there is little distinction between fewer animals generally, or fewer animals in the traditional hunting grounds in particular, if you are relying on the migration for your survival. Shortly before Tolstoy was in the area, Thierry Mallet was also there. He observed a large number of the local Inuit fishing on the ice, which he immediately knew was bad. "Fishing, was our thought, and at once we knew that our friends were in a bad way. No Eskimo fishes inland through the ice in winter unless he has missed the herds of caribou in the fall and has been unable to stock up with meat and fat until the next spring."

The failure of the caribou did not go unnoticed, even by people who could survive the failure. In 1947 the American naturalist Francis Harper came to Nueltin to study the barren ground caribou, and that resulted in his book Caribou of Keewatin. It also resulted in the perhaps better known books The People of the Deer and Never Cry Wolf, which were written by Francis' young research assistant, Farley Mowat.

These days, of the 11 different caribou population units in Canada, half of them are endangered. And some are "extirpated", or locally extinct. That means, for instance, that while the herd that used to roam Prince Edward Island is not technically extinct, and still exists on the mainland, you nonetheless won't find any animals on the island. This is true in isolated mountain environments too. There used to be 17 herds of southern mountain caribou in B.C., but now there are 13. Two of them became extirpated in 2019.

In order to combat the decline, the B.C. government spent two million dollars in 2019 to kill 500 wolves. Fortunately, Farley was already dead for five years at this point as news of someone killing wolves in order to save caribou would surely have killed him. Wolves are the main predator of caribou in the mountains, and they are able to track and kill caribou much more easily these days because the forest, even in the mountains, is being cut up for various reasons including pipelines and snowmobile trails. Caribou are suspicious by nature, so they will avoid any disruption in the forest. Criss crossing trails of any sort limits the caribou's mobility, but greatly increases that of the wolves, who have no problem with trails. The jury is out on whether this cull has had any effect - as the Inuit say, "The caribou feeds the wolf, but it is the wolf who keeps the caribou strong". But wolves aren't the only problem in any event, of course. Wolverines, golden eagles, foxes, bears and even insects all eat caribou - the latter can take a litre of blood from an adult animal in the course of a week, causing it to stop feeding and become weak, and attract larger predators. The largest predator, of course, is the polar bear. And in Svalbard, one study showed that 27% of polar bear scat used to be reindeer.

Then, of course, there is disease. The white-tailed deer is partially immune to the brainworm that it carries, but it is a vector of that disease for other animals such as the caribou, who are not immune to it. One of the symptoms of brainworm in caribou is a loss of fear of humans, quite often a fatal affliction.

In North America, the Greenland caribou became extinct in 1900 and the Dawson's caribou twenty years later. The Peary caribou is endangered, its numbers declining by 72% over the last few generations. The caribou on the quarter is merely threatened, but some individual populations are endangered or extirpated.

Oddly enough, the barren-ground caribou and in particular the Qamanirjuaq herd is not currently threatened, although the herds are declining, as any of the local Dene or Inuit will tell you.

So let's go to Nueltin Lake, and maybe we'll see some caribou!

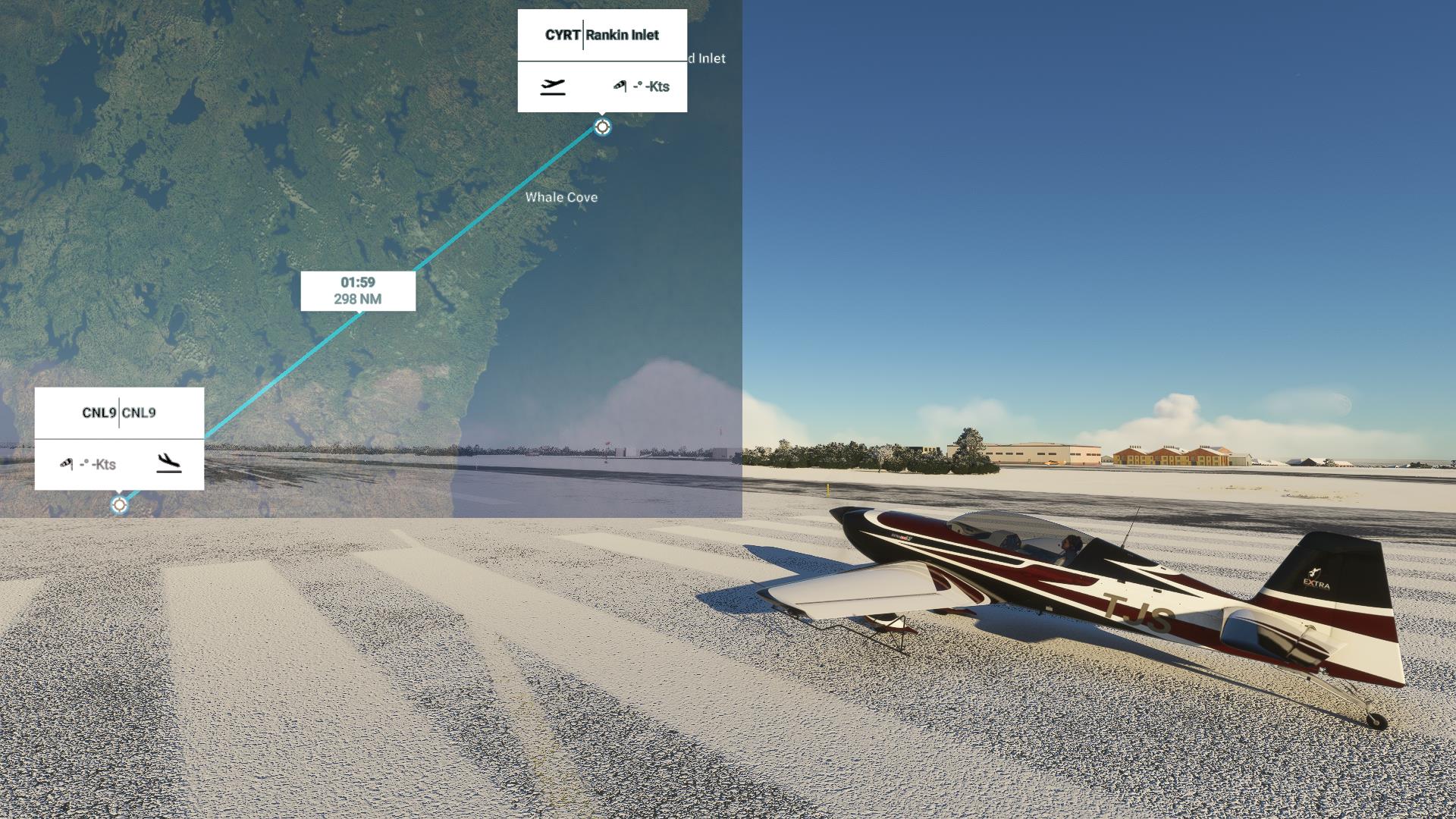

Rankin Inlet's got a really nice airport.

Rankin Inlet's got a really nice airport.

|

Considering where it is.

Considering where it is.

|

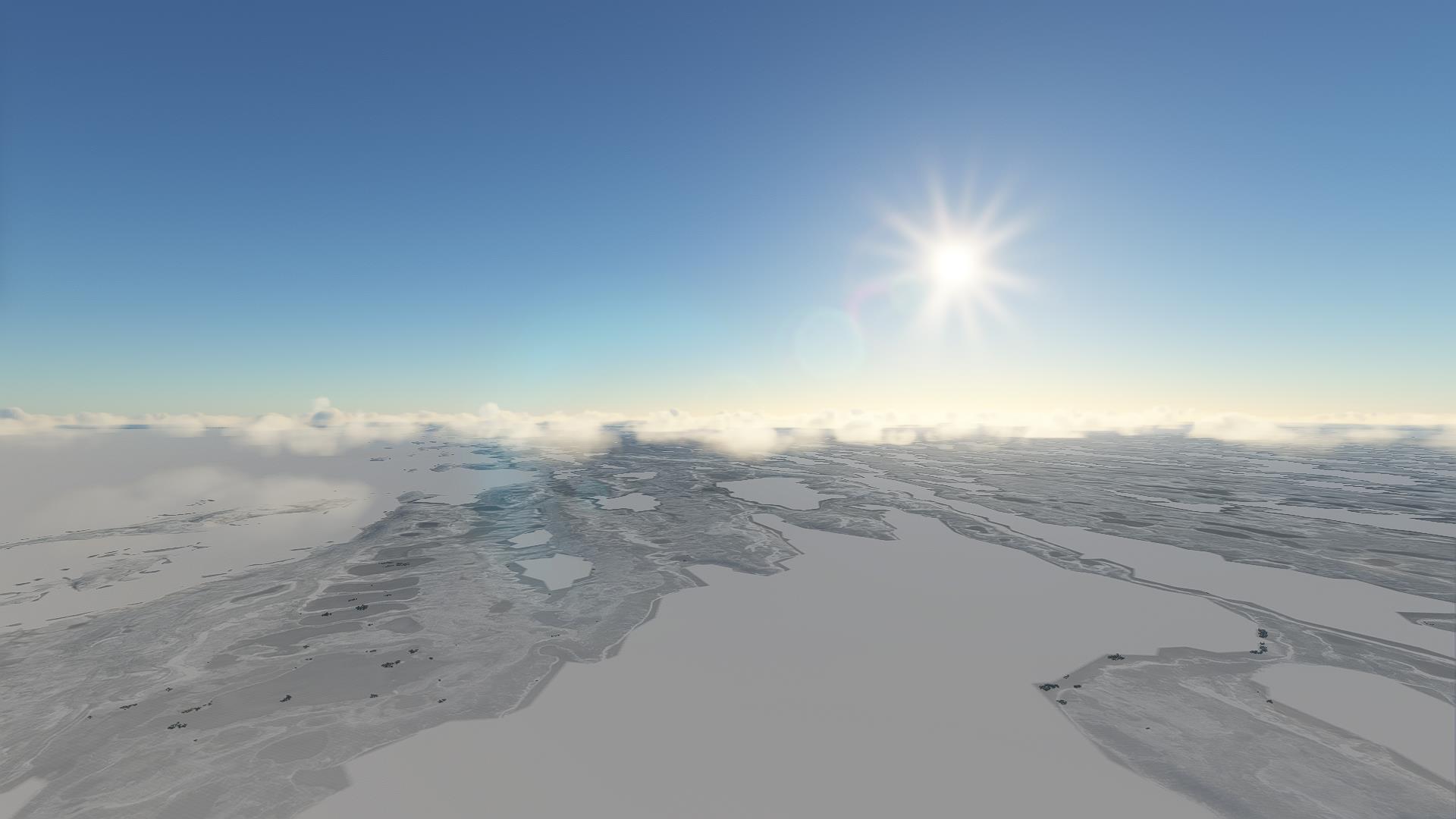

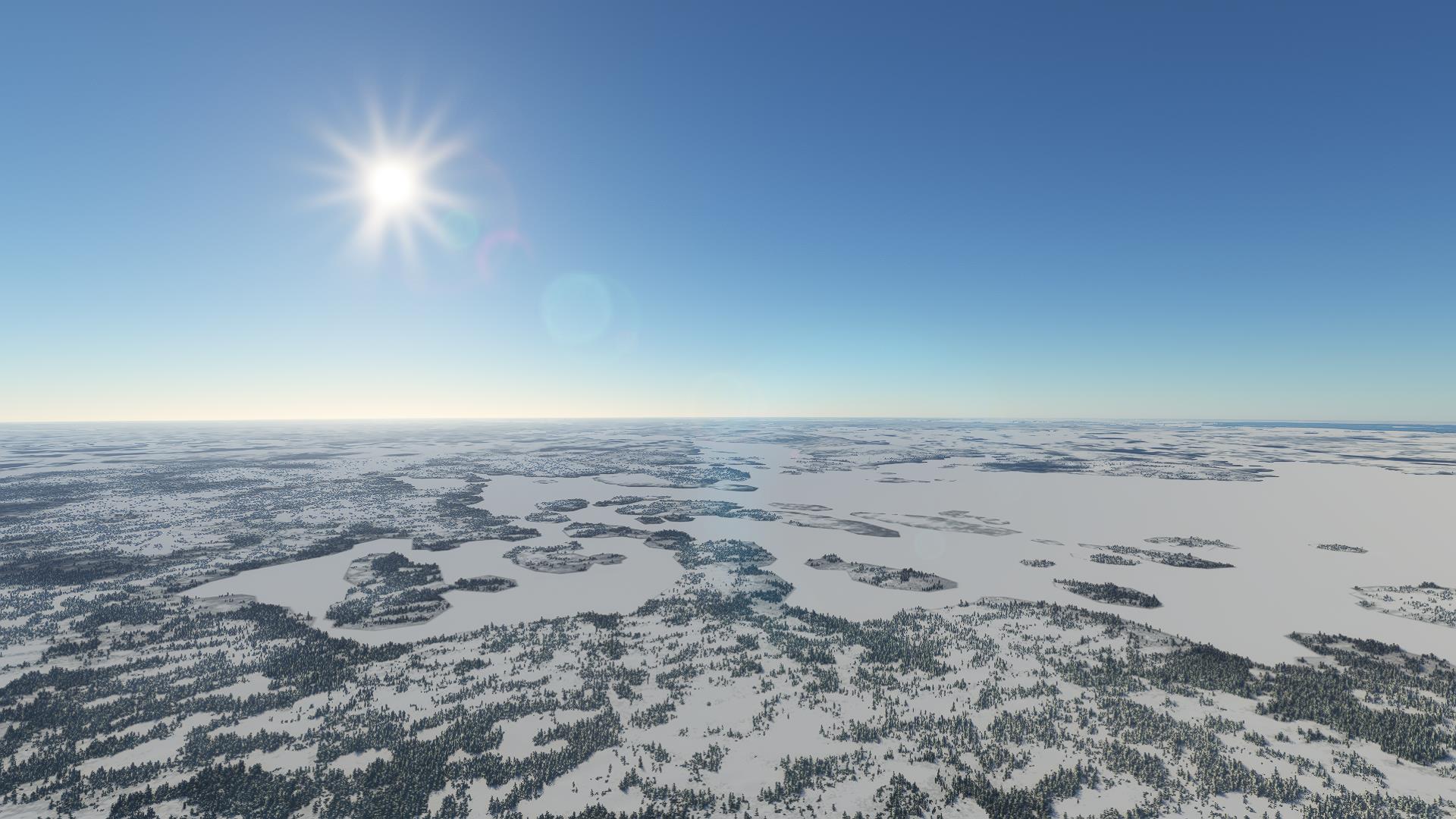

This will be the scenery for some time. Little sticks.

This will be the scenery for some time. Little sticks.

|

That means we're coming up on Nueltin Lake.

That means we're coming up on Nueltin Lake.

|

Apparently this is the airport.

Apparently this is the airport.

|

It's really more sort of a field. Anyhow, it's home for the night. Tomorrow we're off to Big Sky Country.

It's really more sort of a field. Anyhow, it's home for the night. Tomorrow we're off to Big Sky Country.

|